Collecting data during COVID-19: How do we address data quality?

At a time when everyone is confined to stay in their houses because of the COVID-19 pandemic, institutions working on primary data collection, with deadlines looming and no clear vision of future field trips, are looking at alternatives for conducting surveys. One of them being phone survey.

As per the ‘Household Survey on India’s Citizen Environment & Consumer Economy’ (ICE 360° survey) conducted in 2016, 88% of households in India today have mobile phones and, as of December 2019, over 77% of Indians have access to wireless broadband through smartphones. However, according to the latest figures available from 2019, India also has a literacy rate of only 69%, with 22% of the population living below the national poverty line.

Now, in order to conduct a large-scale study that requires answers from both the rural as well as urban households, from the poor to the rich, from literates and illiterates, the mode of communication can critically influence the efficacy of the study.

It is a fact that most of us are annoyed when we are showered with questions over the phone. We cooperate for a while and then either disconnect (at times sending the phone number directly to our ever increasing blocklist) or answer, just for the sake of it. Who is going to verify anyway? Also, this is not just me; I am sure, you too request the caller to call back later when you are in the middle of piles of work (whether that’s office work or household chores or just plain relaxing) — a typical reaction to any survey conducted over phone.

The dilemma of choosing the best mode of communication:

There are various ways of conducting phone surveys:

- Interactive voice response (IVR) or automated voice surveys: both literates and illiterates can answer survey questions by simply pressing the required buttons on their keypads.

- Short message service (SMS) that requires text messaging: respondents can answer whenever it’s convenient and wherever it suits them.

- WhatsApp (this would require internet services): these days most people owning a smartphone are active in WhatsApp, resulting in higher response rates.

- Computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI): surveyors can just concentrate on the interview as the routing instructions are taken care of, making the whole process more efficient and quicker.

- Phone calls: provides scope of gathering valuable information or anecdotal evidence from conversation with respondents.

While the mode of communication is critical to the kind of response rate one gets, each of them has their pros and cons. For instance, while IVR, SMS and even WhatsApp, are all low-cost methods, they lack a personal or human touch. Moreover, a survey might not be as efficient if the questionnaires are targeted to specific audiences, such as married women, while the phones are owned by their husbands or other members. Similarly, CATI has been a reliable way of conducting telephonic surveys but the current lockdown has also shut down call centres. As a result, phone calls, despite not being the cheapest mode of conducting surveys, have emerged as the best possible way of reaching out to all sections of the population.

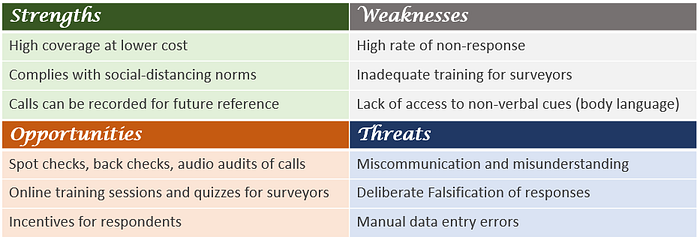

While the mode of communication is critical to the kind of response rate one gets, the larger implication is on data quality. The SWOT analysis below shows that conducting surveys with telephone provides significant challenges alongside several opportunities.

Deep dive into the challenges of conducting phone surveys through calls:

- With the rising number of bank frauds through fake calls in India, phone surveys seeking personal information often risk being misconstrued for phishing calls. Simultaneously, duration of such surveys exceeding 15 mins or so can lead to restlessness and lack of cooperation from the respondents.

- For households with one mobile phone, conducting a wholesome survey can be challenging due to time constraints placed on the use of the device. It may also be very difficult to speak to the same member of the family on follow-up calls. Also, with all members confined to a common space due to the lockdown imposed, the respondent can often hesitate to be honest in front of the other members, thereby, truth often being replaced by socially acceptable answers. This is also because respondents might find it difficult to trust strangers with personal information. Adding to that is the chaos of an entire family trying to facilitate work within a house, resulting in misunderstanding of questions, miscommunication and incorrect entry of responses.

- More importantly, in households where women are already victims of domestic violence, keeping them engaged over the phone with a stranger asking a series of personal questions often aggravates the situation.

- In addition to that, irregular network coverage across areas in India also pose serious challenges. In an article published by BBC, Roy quoted Claire Verhagen on her first encounter with India when she landed in Delhi and switched her phone on, at first she was not able to connect to any of the networks and then experienced frequent call drops. Such frequent call drops or busy networks often lead to no responsiveness or incompleteness of the survey.

- On the other hand, the surveyors’ knowledge about the survey and its purpose is also crucial. The quality of data suffers greatly if the surveyor is unsure of the questions, if their dialect or accent is not pleasant or hard to interpret and if the speed of their speech is not desirable. Proper training of surveyors ensuring uniform standards across geographically diverse survey locations is, therefore, important and is a new challenge in the time of COVID-19.

- It is also to be remembered that not all questions are relevant to everyone. The problems of the rich are vastly different from those of the poor. So, it is crucial to have customized questionnaires. Now, gauging a person’s social status over a phone call is almost impossible and many might find related queries to be intruding.

Therefore, with a shrinking sample size and an unreliable set of data, the quality of telephonic surveys becomes questionable. Studies derived from such data can have serious flaws in outcomes and as a result effective policy making is hindered.

So, in times like these, when phone-based surveys seem to be the only choice, how do we ensure data quality and integrity?

- Firstly, it might be helpful to have non-verbal IVR options (such as dialling a number) within the call to understand which language the respondent prefers, the annual income of the family, questions about sexual health and other sensitive questions, if needed. Those might make the situation less awkward, gain confidence of the respondent and increase the likelihood of receiving correct answers. The surveyor can then ask questions that are customized for the options selected.

- Secondly, live audio audits involving conference calls, looping in a Subject Matter Expert (SME) during the survey can help keep a track of the data collected. When live checks are not possible, surveys should be recorded, and random back checks performed to ensure compliance with standards. Regular feedback or creation of dashboards marking the progress of each surveyor on a timely basis, considering indicators like the quality of the calls, punctuality of the surveyors, duration of the calls, questions covered and more can also help keep a check on surveys. Meting out performance incentives might result in better performance by surveyors.

- Thirdly, conducting online training and quizzes, testing the surveyors by giving them scenarios and checking their understanding might help prepare them better. To get good quality data, it is important to ensure that the interviewer himself can judge the responses.

- Fourthly, Machine learning or use of Artificial Intelligence in dialect or speed detection can also make it easier for supervisors to check whether the usual norms are being followed by the surveyors. Also, one can use Natural Language Processing (NLP) to parse answers to any open ended question.

- Fifthly, as a golden rule for all surveys, it is important to keep the survey short so that neither the surveyor nor the respondent gets restless. A section-wise or module-wise survey might help in shortening the call time. However, this might also lead to calling the respondent frequently. To address the latter problem, respondents could be offered motivational incentives such as phone recharges. Recharging numbers with limited validity of 15 days or so could mean that the same incentive could be offered for the next round of survey. During these unprecedented times, when most households have unsteady flow of incomes, such incentives could encourage most respondents to ensure continued participation.

- Finally, a chain referral sampling technique can also increase response rate, for example., asking the respondent to share five other phone numbers from their contact list belonging to different households could help gather numbers that are in working condition. This respondent driven sampling also ensures reaching to the right kind of people for the survey.

Given that these are indeed unusual times, the age-old methods of conducting surveys are not so obvious anymore. Researchers are forced to think out of the box. It is true that the percentage of phone numbers that are permanently switched off, are outside network coverage, unreachable or go unanswered is significantly high, resulting in a higher non-response rate. Nevertheless, out of all the possible options of conducting surveys, at a time when social distancing has become the norm of the day, the new normal is to conduct phone surveys that ensure high coverage at a low cost and within less time. However, this blog just reflects my thoughts from the limited exposure I’ve had. There could be several other ways to deal with these above challenges, perhaps an AI based chatbot survey!

I will be happy to know if you have come across similar experiences or discovered new strategies to overcome such challenges. If there is a different way to improve the quality of data from phone surveys or to engage respondents better or to make the whole process more efficient, please feel free to share your thoughts with us, we will be happy to learn from you.

This blog was written as part of National Data Quality Forum (https://www.ndqf.in/) under the DataQi project. This project aims to strengthen India’s data eco-system by innovating and institutionalizing solutions on data quality and analytics.

You can also share your thoughts or feedback about this blog by writing to me directly at tchaudhuri[at]popcouncil.org